Anton Bruckner in Lucerne

Born 200 years ago, the Austrian composer made a visit to Switzerland 144 years ago

Anton Bruckner certainly had experience traveling across Europe: his concert tours as an organist took him to Paris, Nancy, and London, for example, while his enthusiasm for Wagner enticed him to undertake trips to Bayreuth and Munich. However, Bruckner enjoyed only one extended vacation trip, an excursion meant purely for pleasure. Via Oberammergau, where he attended the Passion Play, his itinerary led him to Switzerland in late August and the first days of September in 1880 – including a stop in Lucerne.

Bruckner wanted to learn more about the organs of Switzerland, but he especially wanted to encounter the highest peak in the Alps, Mont Blanc. So he completed the first part of his tightly timed Swiss tour at a rapid pace. Coming from Munich and Lindau via Lake Constance, Bruckner traveled directly to Geneva and on to Chamonix after a detour to the Rhine Falls near Schaffhausen and a three-day stop in Zurich, where he played the organ in the Grossmünster and hiked to Rapperswil, among other adventures. Once there, however, he ran out of luck: due to bad weather, Bruckner had an opportunity only to marvel from a distance at the Mont Blanc region on his second trip to La Flégère.

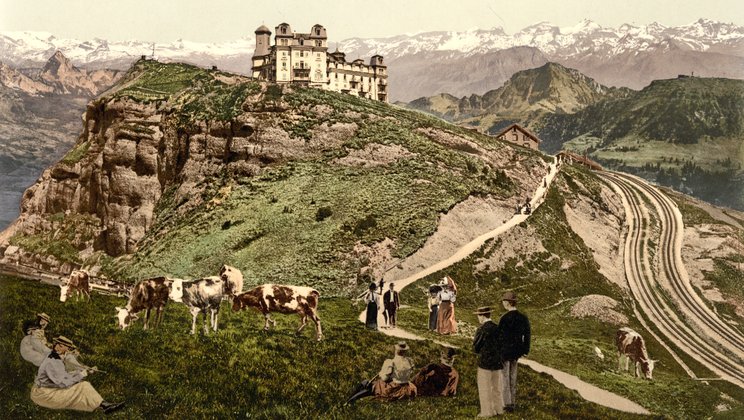

On the way back, Bruckner then took some more time to explore the neighboring country. Via Geneva, Lausanne, Fribourg, and Bern, he made his way to Lucerne, where he stayed from 8 to 10 September. From Vitznau, Bruckner took the cogwheel railroad, which had opened nine years earlier as Europe’s first mountain rack railway, up to Rigi Kulm. He spent the night on the summit and enjoyed the view of the Bernese Alps at sunset and sunrise.

Bruckner noted in his pocket diary: “Bernese Alps magnificent.” Then, somewhat enigmatically, follows this observation: “You can see over low or sloping mountain peaks to other distant ones; the more distant the others, the better; likewise: the more sloping.” This probably means that because the peaks on the other side of Lake Lucerne are neither too high nor too close together, i.e., because they do not obstruct the view, the result is a staggered mountain panorama that enhances the grandeur of the distant Alpine massif. Of course, Bruckner also took the opportunity in Lucerne – as in the other Swiss cities he had visited – to get to know local organists and their instruments. In Lucerne, these were Father Ambros Meier, organist of the Hofkirche St. Leodegar, and the grand organ located there.

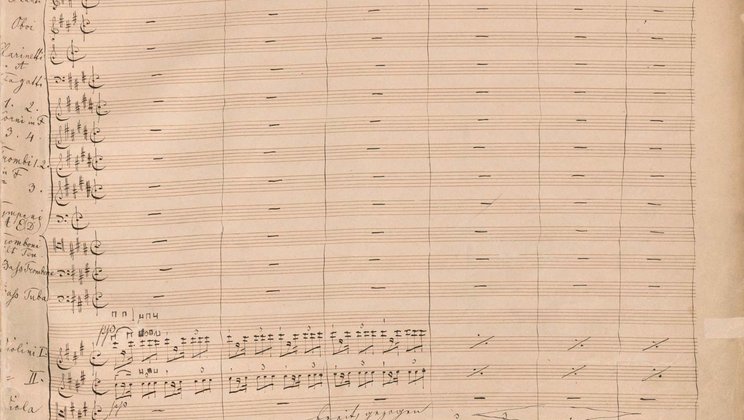

Bruckner’s trip to Switzerland also coincided with his work on the Sixth Symphony, which he had begun the previous year and was able to complete the following year. Immediately after his return to Vienna, he immersed himself in the first movement, which he completed on 27 September. Some commentators have even made a direct connection between its unusual opening and Bruckner’s vacation impressions. The Sixth does not begin with the mysterious string tremolo that is so typical of Bruckner’s other symphonies. Instead, it gains momentum from the outset with a concisely rhythmic repetition of notes in the violins, in a way that is reminiscent of the rousing finale of Felix Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony: an echo, perhaps, of the rattling train?

Bruckner himself is said to have called his Sixth his “cheekiest” symphony. It remains to be seen whether this was simply due to the fact that the adjective rhymes with “sixth” in German (Sechste: keckste) or actually expressed the exuberant vacation mood the music may have conveyed. Either way, the fact that Andris Nelsons and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra are performing this work in particular at their Lucerne guest performance on 4 September – precisely on Bruckner’s 200th birthday – is a wonderful coincidence. But you can hear many more of his symphonies at Lucerne Festival in the 2024 Bruckner Year: the First (with Christian Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic), the Fifth (with Kirill Petrenko and the Berliner Philharmoniker), the Seventh (with Yannick Néztet-Séguin and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra), and the Ninth (with Lahav Shani and the Munich Philharmonic), as well as a recomposition of the Seventh Symphony by Stegreif, the “improvising orchestra” from Berlin.

Another vacation impression seems to linger in Bruckner’s Sixth Symphony. At the Passion Play in Oberammergau, the 56-year-old was smitten by one of the amateur actresses, the 17-year-old Marie Bartl. She rejected his typically hasty proposal of marriage. But they remained in contact via correspondence for months – a fact that distinguishes Marie Bartl from the many other female acquaintances (mostly just admired from afar) Bruckner meticulously noted in his pocket diary. (“On the 2nd floor of the station at the 1st window, Miss [X] looked down twice. Is this a stranger? where from? etc.? Wonderful,” he notes with regard to the train arriving in Lucerne.) It may therefore be more than coincidence (or more than pure Wagner worship) that the Adagio of the Sixth repeatedly echoes the “Mild und leise” Liebestod melody from Tristan und Isolde.

Incidentally, it took some time not only for the composer but also for his music to reach Switzerland. Not until November 1896, 16 years after Bruckner’s Swiss tour, were excerpts from his Seventh Symphony heard in Switzerland, in Lucerne: this is the first documented performance of one of his works in this country. The popular Seventh was also the first Bruckner symphony to be performed at Lucerne Festival: Hans Münch led the Swiss Festival Orchestra in a performance in 1943. Bruckner’s Sixth Symphony was first performed ten years later by Rafael Kubelík.

Malte Lohmann | Editorial

Translated by Thomas May

-

Sat 24.08.Lucerne Festival Orchestra 5

Lucerne Festival Orchestra | Yannick Nézet-Séguin | Beatrice Rana

Date and Venue

Sat 24.08. | 18.30 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

Schumann | BrucknerVaillant - Main SponsorSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 40 -

Wed 28.08.Berliner Philharmoniker 1

Berliner Philharmoniker | Kirill Petrenko

Date and Venue

Wed 28.08. | 19.30 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

BrucknerZuger Kantonalbank - Concert SponsorSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 40 -

Wed 04.09.Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra | Andris Nelsons | Daniil Trifonov

Date and Venue

Wed 04.09. | 19.30 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

Mozart | BrucknerZurich Insurance - Main SponsorSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 40 -

Sat 07.09.Vienna Philharmonic 2

Vienna Philharmonic | Christian Thielemann | Julia Hagen

Date and Venue

Sat 07.09. | 19.30 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

Schumann | BrucknerUBS - Main SponsorSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 40 -

Tue 10.09.Stegreif

Stegreif – The Improvising Symphony Orchestra

Date and Venue

Tue 10.09. | 18.00 | KKL Luzern, Lucerne HallProgram

BrucknerSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 50 -

Fri 13.09.Munich Philharmonic

Munich Philharmonic | Lahav Shani

Date and Venue

Fri 13.09. | 19.30 | KKL Luzern, Concert HallProgram

Bach | BrucknerKPMG AG - Concert SponsorSummer Festival 2024starting at CHF 40